So far we’ve looked at a number of forgotten filmic curios amidst discussions of more familiar Disney movies. Today we’ll be taking a quick look at what may be the oddest film produced by Walt Disney Productions: 1943’s Victory Through Air Power.

Based upon the 1942 book by Russian expatriate Major Alexander P. de Seversky, the movie is basically an illustrated (or rather animated) lecture, in which de Seversky (who appears in the film) spells out his theories regarding the importance of an airborne fighting force in the currently-raging World War. Walt Disney had read de Seversky’s book and, his righteous patriotism inflamed, immediately began production on a filmed version, paying for the endeavor personally. Besides being a case of “putting his money where his mouth was,” this self-funding may have been necessary due to the studio’s poor cash-flow at the time (noted in previous posts.) Production was pushed ahead at a feverish pace, as Disney felt the speed by which he could present de Seversky’s message was of the utmost importance. Aimed primarily at government officials and military decision-makers, it’s somewhat surprising (especially from today’s perspective) that such a work of persuasive propaganda, created at the behest of the head of a major movie studio, would even get made - let alone released to the public.

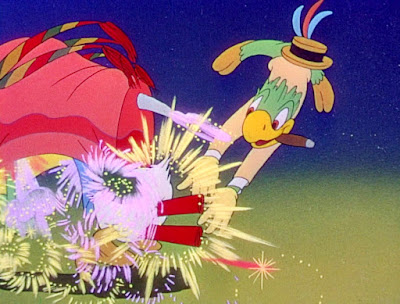

The film opens with a lengthy “History of Aviation” segment, which presents a humorous look at the progression of aeronautics. Much like the lightweight “Cold-Blooded Penguin” sequence which opens the otherwise manic The Three Caballeros, this segment orients the audience to expect the airy style of humor associated with the studio’s cartoon shorts - making the serious feature that follows all the more impactful. Despite it’s silly humor, this opening segment is fascinating nonetheless, as it presents viewers with some interesting historical tidbits. For example: did you know that the very first airplane developed for the U.S. military was designed and built by the Wright brothers? Well, now you know … and knowing’s half the battle.

|

| Only vun ving? Very interestink... |

For the live-action sequences, in which de Seversky addresses the camera directly, Disney chose H.C. Potter to direct. Potter was a respected working-director whose previous credits included 1941’s Helzapoppin (a film whose title I attempt to inject into as many conversations as possible,) and Disney felt it best to have an already established "Hollywood man" to assist non-actor de Seversky in his performance. It seems like it paid off, since the heavily-accented de Seversky comes across as quite natural; he is kept moving around the small set (meant to look like a military office, one assumes,) frequently gesturing with his hands and making steady emphases to keep from drifting into droning monotony.

|

| Victory Through Power Suits |

It helps, of course, that de Seversky is backed up by animated maps and charts created by some of Disney’s foremost artists. Direction of the animated sequences was spread amongst three of the studio's best visualists: James Algar, Clyde Geronimi and Jack Kinney. As a result of the film’s rushed production, much of the animation on display is more limited than in the studio's other features. The clear and direct animation, however, actually helps to break down and illustrate the sometimes complex concepts of military strategy and supply-lines to audiences; de Seversky’s points are not only made comprehensible, but all the more persuasive.

|

| The Americas are blocked in by a yellow daisy and an evil Trivial Pursuit piece |

It also doesn’t hurt that Disney, clearly all-in with the arguments presented, has no problems “fanning the flames” of a nation at war. Viewers are therefore presented with a short animated summary of the war up to that point, which portrays the German military machine as a foreboding monster ploughing mercilessly over much of Europe. Despite continued attacks from the occupied mainland, England is portrayed as bravely holding back the machine with its dedicated Royal Air Force. This sequence is capped off by a brief but potent animated reenactment of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor - which surely would’ve struck a raw nerve in the minds of the U.S. audience.

As the discussion proceeds, the associated imagery slowly becomes more fanciful. Once the film has adequately demonstrated the futility of ground assaults against a well-defended perimeter surrounding the enemy’s centers of military production (demonstrated by a circular “hub-and-spoke” metaphor - curiously, an idea that would later well-serve the design of Disneyland,) a number of possible “flying fortress” prototypes are demonstrated. The strength and ferocity which dramatizes some of these possible “Axis-destroyers” is sometimes alarming - such as the large bomb that would be designed to strike fault-lines below the surface of an enemy city, creating a factory-destroying earthquake. It’s no surprise that the British Royal Navy, impressed with the film’s demonstration of a concrete-breaching bomb that could potentially destroy German U-boat pens, soon developed its own 4,500-pound “bunker buster” - nicknamed “the Disney bomb.”

|

| Ka-boom! |

The final sequence of the film, unaccompanied by narration (though preceded with a “ra-ra” final rally from de Seversky,) dramatically imagines an air-powered U.S. armed force striking at the well-defended island of Japan. As the repeated air-strikes intensify, the island nation (and it’s far-reaching military force) morph into a giant Octopus, it’s tentacled limbs stretching over the Pacific. The air-forces soon change into a screaming Bald Eagle (naturally,) which strikes at the Octopus with it’s gleaming talons until the beast lays dead. The Japanese war machine now a smoking wreck, the Eagle flies back across the sea, coming to rest atop a high-flying U.S. flag, ending the film on a not-so-subtle bit of patriotic propaganda. The animation on display in this sequence reaches such a dark intensity, the closest parallel I can think of is Gerald Scarfe’s animation for Pink Floyd’s The Wall, produced decades later.

|

| Gonna fly like an eagle... |

Victory Through Air Power is a hard film to categorize (and review!), beyond the fact that it’s non-narrative; part history lesson, part propaganda film, and part persuasive essay, the film is one few have seen or heard of. During its theatrical releases in 1943 and ‘44 (and making the rounds in the United States and British war offices,) the film was received rather poorly by an uninterested public. Though the “History of Aviation” segment was later shown separately as a short-feature, the film in it’s entirety would go unseen for decades, outside of the occasional print surfacing in film-study courses or at underground animation festivals. It wasn’t until 2004 that Disney officially released the film on DVD, as part of its “Walt Disney Treasures” line of collector’s releases (accompanied by an introduction by the ever-hyperbolic Leonard Maltin, who claims that the film “changed FDR’s way of thinking” about air power - despite the fact that the U.S. had decided to pursue long-range bombing two months before Roosevelt saw the movie.)

Unlike most of Disney’s other animated (or mostly-animated) features, however, this “odd duck” was made for specific and time-sensitive purpose, rather than timeless entertainment.

|

| USA! USA! USA! |